Freedom › Confusions

Bradley, Francis Herbert. 1876. Ethical Studies. Henry S. King and Co.: London

[51] If ‘must’ always means the ‘must; of the falling stone, then ‘must’ is irreconcileable with ‘ought’ or ‘can.’ Freedom will be a bare ‘not-must,’ and will be purely negative.

But how if the ‘must’ is a higher ‘must’? And how if freedom is also positive—if a merely negative freedom is no freedom at all? We may find then that in true freedom the ‘can’ is not only reconcileable with, but inseparable from, the ‘ought;’ and both not only reconcileable with. but inseparable from, the ‘must.’ Is not freedom something positive? And can we give a positive meaning to freedom except by introducing a will which not only ‘can,’ but also ‘ought to’ and ‘must,’ fulfil a law of its nature, which is not the nature of the physical world.

[52] We all want freedom. Well then, what is freedom? ‘It means not being made to do or be anything. ‘Free’ means ‘free from.’’ And are we to be quite free? ‘Yes, if freedom is good, we can not have too much of it.’ Then, if ‘free’ = ‘free from,’ to be quite free is to be free from everything—free from other men, free from law, from morality, from thought, from sense, from—Is there anything we are not to be free from? To be free from everything is to be—nothing. Only nothing is quite free, and freedom is abstract nothingness. … Freedom now means the self-assertion which is nothing but self-assertion. It is not merely negative—it is also positive, and negative only so far as, and because, it is positive.

Mulford, Elisha. 1877. The Nation. Hurd and Houghton: New York.

[18n.1] There is in the same school the utter denial of the real freedom of the individual and the nation, when it aims to define freedom only in the limitations of a physical necessity, and the mind of man is regarded only as involved in the physical process of nature.

[25] Government, which is the central organization of the nation, is not an evil. Its substance is in itself good, and is implicit in the conception of the good. Law, which is the ground and expression of its authority, is in its ultimate apprehension the manifestation of the divine will, as has been said of it in imperishable words, ‘Its home is the bosom of God, and its voice is the harmony of the world.’ And freedom, which in the nation is constituted in law, is the sphere of the normal development of man. And the nation is not a mere negation, only a restriction of evil tendencies and an impediment to evil courses, as this theory assumes. It has a positive character and content. It is the manifestation of the life of the organic people, after a moral order, and in the institution of justice and of rights. It is a constructive power in history. It is not a local and temporary expedient, and its elements are not those which the scientific culture of another and a later age may set aside.

[110] The action which is merely unlimited and unrestrained is not free; the power to do whatever one lists or pleases is not freedom. The most false representation of freedom is this apprehension of it in the absence of restraint. It is then identified with mere caprice. The freedom which in this assumption is called natural freedom is unreal.

[115] The freedom of the people, or political freedom, subsists in the nation in its organic and moral unity. It is the self-determination of the people, in the nation, as a moral person. It is formed in the conscious life, and its process is in the conscious vocation of the organic people. Freedom has, apart from the nation, no positive existence. Thus among the vast populations of Asia, there is no political freedom, but only the natural freedom of man, and the term freedom can be applied to those peoples only negatively as denoting the absence of a positive system of slavery.

[117] Freedom, in the assertion of law, assumes restraint and accepts obligations in the relations of an organic and moral being, and in these there is no limitation in the sense of hindrance, or as the mere impediment to action.

[119-120] The realization of the freedom of the nation, or political freedom, is in rights. Freedom embodies itself in rights, as in rights also there is the manifestation of personality. The institution of positive rights defines in the nation the sphere of a realized freedom. … The freedom of the people as it becomes determinate establishes itself in rights…. It is only in rights that freedom is actualized in the nation; it is only in positive rights that it gains a sure foothold in its progress; they alone afford the requisite strength and security for it. In rights freedom is guarded against denial, fortified against fraud, shielded against conspiracy and surprise and sudden overthrow. In the same measure in which freedom fails to establish itself in rights, whose institution is in law, it is liable to the whim and the caprice of men, and the highest interest is left to the adjustment of changing circumstance. This secure institution and organization of freedom in positive rights is the work of the statesman. It demands the more comprehensive political sagacity. Freedom does not gain much while it is held in an ideal conception, and is left to the pages of scholars, or the rhymes of poets, or the voices of orators. These are not laws, and the condition of every advance in freedom is its assertion in laws and its organization in rights. It has in their strong guaranties alone protection against selfish interests and private aims.

Leslie, Thomas Edward Cliffe. 1879. Essays in Political and Moral Philosophy. Longmans, Green and Co.: London.

[19-20] But practical freedom involves much more than the absence of legal and social restraint; every limitation of power is an abridgement of positive liberty. A man is not free to go from Shropshire to London, or from Liverpool to New York, if the journey is too long and expensive for him; nor is he actually free to develop a powerful intellect if education lies beyond his reach. The present multiplicity of occupations, pursuits, and paths of thought, affords the requisite variety of situations; and a nominal freedom has arisen from the abolition of many feudal, municipal, and religious disabilities; but it is the facility of information and locomotion, the accessibility of books, newspapers, and places, that give real freedom to the poor.

Arnold, R. Arthur. 1880. Free Land. C. Kegan Paul & Co.: London.

[12] The argument of this book will be directed to securing the freedom of the soil; that is, its freedom from the operation of those laws and customs which, with injury to every class in the country, maintain an unnatural and injurious distribution of the land. … I have no objection to such a distribution of the soil if it should result from the action of laws which are most beneficial alike to the interests of proprietors and to those of the community.

[278-79] There would be quite a different administration of the Poor Law of England when free land was established and an enfranchised people ruled in all departments of local expenditure. The landowner's ability to pay would further be immensely increased by the augmented value of his land—not merely owing to comparative freedom from pauperism, but by the positive increment of value contributed by security of title and simplicity of transfer.

Ormond, A. T. 1880. “Agnosticism in Kant,” Princeton Review 56(Nov.): 351-382.

[376] We must postulate something. First, in order that the unqualified law of duty may be valid man must be free. He must be free not only as transcending the laws of sense which is negative freedom merely, but as subject to laws which transcend sense. Negative freedom is consistent with mere lawlessness and could not account for the fact of obligation. But positive freedom presupposes law. If man is free in the positive sense, he not only transcends the laws of sense but is subject to super-sensual laws.

Green, Thomas Hill. [1881] 1888. “Liberal Legislation and Freedom of Contract” in Works of Thomas Hill Green, Vol. III, edited by Richard Lewis Nettleship. Longmans, Green, and Co.: London.

[370-371] But when we thus speak of freedom, we should consider carefully what we mean by it. We do not mean merely freedom from restraint or compulsion. We do not mean merely freedom to do as we like irrespectively of what it is that we like. We do not mean a freedom that can be enjoyed by one man or one set of men at the cost of a loss of freedom to others. When we speak of freedom as something to be so highly prized, we mean a positive power or capacity of doing or enjoying something worth doing or enjoying, and that, too, something that we do or enjoy in common with others. We mean by it a power which each man exercises through the help or security given him by his fellow-men, and which he in turn helps to secure for them. When we measure the progress of a society by its growth in freedom, we measure it by the increasing development and exercise on the whole of those powers of contributing to social good with which we believe the members of the society to be endowed; in short, by the greater power on the part of the citizens as a body to make the most and best of themselves. Thus, though of course there can be no freedom among men who act not willingly but under compulsion, yet on the other hand the mere removal of compulsion, the mere enabling a man to do as he likes, is in itself no contribution to true freedom. In one sense no man is so well able to do as he likes as the wandering savage. He has no master. There is no one to say to him nay. Yet we do not count him really free, because the freedom of savagery is not strength, but weakness. The actual powers of the noblest savage do not admit of comparison with those of the humblest citizen of a law-abiding state. He is not the slave of man, but he is the slave of nature. Of compulsion by natural necessity he has plenty of experience, though of restraint by society none at all. Nor can he deliver himself from that compulsion except by submitting to this restraint. So to submit is the first step in true freedom, because the first step towards the full exercise of the faculties with which man is endowed.

[372] If I have given a true account of that freedom which forms the goal of social effort, we shall see that freedom of contract, freedom in all the forms of doing what one will with one's own, is valuable only as a means to an end. That end is what I call freedom in the positive sense: in other words, the liberation of the powers of all men equally for contributions to a common good. No one has a right to do what he will with his own in such a way as to contravene this end. It is only through the guarantee which society gives him that he has property at all, or, strictly speaking, any right to his possessions. This guarantee is founded on a sense of common interest.

Jevons, William Stanley. 1882. The State in Relation to Labour. Macmillan and Co.: London.

[13-14] If we are to acknowledge the existence in social affairs of any indefeasible right or absolute principle, none would seem more sacred than the principle of freedom—the right of the individual to pursue his own course towards his own ideal end. In favour of such a view, it may be said, in the first place, that happiness mainly consists in unimpeded and successful energising. Every needless check or limitation of action amounts to so much destruction of pleasurable energy, or chance of such. Not only, however, must man, in common with the brutes, suffer from endless material checks and obstacles, but he cannot enjoy the society of other men without constantly coming into conflict with them. The freedom of one continually resolves itself into the restriction of another. In any case, then, the mere fact of society existing obliges us to admit the necessity of laws, not designed, indeed, to limit the freedom of any one person, except so far as this limitation tends on the whole to the greater average freedom of all.

[15] I do not think that such interference, applying, as it would do, only to the simpler physical conditions of the body, can be said, in a reasonable point of view, to dimmish freedom. As physical conditions become more regulated, the intellectual and emotional nature of man expands ever more freely. The modern English citizen who lives under the burden of the revised edition of the Statutes, not to speak of innumerable municipal, railroad, sanitary, and other bye-laws, is after all an infinitely freer as well as nobler creature than the savage who is always under the despotism of physical want. He is far freer, too, than the poor Indian who, though perhaps unacquainted with written law, is bound down by the most inflexible system of traditional usage and superstition. It is impossible, in short, that we can have the constant multiplication of institutions and instruments of civilisation which evolution is producing, without a growing complication of relations, and a consequent growth of social regulations.

Thompson, Robert Ellis. 1882. Political Economy. Porter and Coates: Philadelphia.

[50-52] It is, therefore, apart from all merely ethical considerations, a wise economic policy for a nation to guard the lives and the health of its people, and to remove all artificial obstructions to the natural growth of population. It is indeed the duty correlative to its right to command their lives and persons in its own defence; but it is also the best policy, in view of both the military strength and the industrial welfare and contentment of its people. For the more people there are productively employed in any well-managed country, the greater the share of food and clothing, of necessaries and comforts, that will fall to each one of them. Whatever tends to diminish their numbers, —or, what comes to much the same thing, to lower their bodily health and strength—has also the tendency to impoverish them by diminishing their power of cooperation and association. … Thus in England the law recently passed to limit the hours of work in mills and factories for married women, received the support of nearly all that class of mill-hands. They were free to make such private contract with the mill-owner as they pleased, but in fact their freedom amounted to nothing whatever until the law required them to refuse excessive work.

Arnold, Matthew. 1883. Culture & Anarchy: An Essay in Political and Social Criticism. Macmillan and Co.: London.

[45-46] For a long time, as I have said, the strong feudal habits of subordination and deference continued to tell upon the working class. The modern spirit has now almost entirely dissolved those habits, and the anarchical tendency of our worship of freedom in and for itself, of our superstitious faith, as I say, in machinery, is becoming very manifest. More and more, because of this our blind faith in machinery, because of our want of light to enable us to look beyond machinery to the end for which machinery is valuable, this and that man, and this and that body of men, all over the country, are beginning to assert and put in practice an Englishman's right to do what he likes; his right to march where he likes, meet where he likes, enter where he likes, hoot as he likes, threaten as he likes, smash as he likes. All this, I say, tends to anarchy; and though a number of excellent people, and particularly my friends of the Liberal or progressive party, as they call themselves, are kind enough to reassure us by saying that these are trifles, that a few transient outbreaks of rowdyism signify nothing, that our system of liberty is one which itself cures all the evils which it works, that the educated and intelligent classes stand in overwhelming strength and majestic repose, ready, like our military force in riots, to act at a moment’s notice.

Gronlund, Laurence. 1884. The Cooperative Commonwealth. Lee and Shepaud: Boston.

[101] Liberty is a negative term; the glorious English word ‘freedom’ is positive. There is the same difference between ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom’ as between ‘right’ and ‘might,’ between ‘fiction’ and ‘fact,’ between ‘shadow’ and ‘substance.’

‘Freedom’ is something substantial. A man who is ignorant is not free. A man who is a tramp is not free. A man who sees his wife and children starving is not free. A man who must toil twelve hours a day in order to vegetate is not free. A man who is full of cares is not free. A wage-worker, whether laborer or clerk, who every day for certain hours must be at the beck and call of a ‘master,’ is not free.

Miller, William Galbraith. 1884. Lectures on the Philosophy of Law. Charles Griffin and Co.: London.

[179-180] While negatively the state must protect the citizen from external force, it may positively assist him to higher freedom when necessary. On the one hand it would secure order, with freedom as the ultimate end in view; and on the other it would promote freedom, which involves order. The state, being an assemblage of conscious moral beings, is itself a conscious and moral being. It has an ethical and spiritual, as well as a physical side. And the philosophy which would confine the state to the functions of a policeman ignores altogether its ethical and spiritual side. … It is this idea of the state which justifies our poor laws. The state (in the widest sense of the word) has brought those persons into existence for its own purposes, and it is bound to see that they do not starve, while it insists on able-bodied men working for their own support, and so adding to the wealth of the community.

[219-220] It is obvious that the struggle between the supporters and opponents of the principle of laissez-faire is merely another example of the opposition between form and matter, to which I have again and again referred. The legal mind tends to support contracts if they are formally correct. If a human being has a spark of self-consciousness, give him freedom of contract and it will do the rest. … And we ourselves, at the end of the nineteenth century, are only now awakening to the fact that freedom of contract is not much more than a theory. If the matter is closely looked into, it will be found there has been not only much less freedom of contract, but much less contract than is generally supposed to be the case.

Montague, Francis C. 1885. The Limits of Individual Liberty. Rivingtons: London.

[3-4] The only proper function of the state is to secure that order within and without which is indispensable if every man is to have an equal chance of doing what he likes. Society exists in order to make the individual free. Once the individual finds himself free, he will develop everything which civilization requires… This doctrine may be called the doctrine of negative freedom… At the present day political and social perfection seem nearly as remote as ever; the ideal which we were about to clasp has melted in our embrace; and we begin to doubt whether the way of seeking after it, once so universally approved, was the only way or the best. For a century of enlarged individual freedom has done for human greatness or human happiness only a very small part of what its noblest advocates expected

[5-6] And for the temper which men cherish towards their society, this temper has been mellowed in England by the habit of emigration, and by legislation which habitually transgresses the principle of laissez-faire; but elsewhere people hitherto seem to have grown more and more discontented as they have attained to more and more freedom.

[7] Our modern Socialism expresses the practical revolt against the doctrine of negative freedom.

[15] If we are indeed enslaved, we have been enslaved of our own free will. The prime occasion of our encroachment upon individual freedom lay in the necessity of organizing some mode of civilized life for the artisans and laboureres crowded together in great multitudes, which made all voluntary action fruitless, and under circumstances which rendered their subsistence more that usually precarious.

[18] The theory of freedom is the theory of the relation sitting between the individual and society.

[49-50] For the doctrine of negative freedom, the doctrine that it is of sovereign virtue for every man, so far as is possible, to do what he likes, the doctrine that we form character by following inclination, rests on a deep-seated doubt as to whether truth and certainty exist at all, and on a deep-seated conviction that the surest good is pleasure, which everybody is likely to pursue of his own accord… Many Liberals of that time wished to apply the fashionable economic principles to the whole of life.

[122] But we must not forget that the old slavery was natural and that the new freedom has been purchased by obedience. In the sphere of science the attempt to liberate our intelligence corresponds to the attempt to liberate our wills in the sphere of action. In either case we obtain freedom only through an arduous discipline. The freedom which we desire is not freedom to do whatever we like, nor freedom to think as we like; but rather freedom from instinct, freedom from our thoughtless natural propensities. This freedom is not freedom to be eccentric. Nor can it be acquired by giving the rein to our eccentricities. Eccentricity is the very thing from which we would be free; what we above all things desire is to be at the center.

[182] Freedom as the complete emancipation of the individual from all social influence is thus an utter impossibility. Happily it is also quite undesirable; the only freedom worth having is the freedom of him who can either control or satisfy all his desires. Complete fruition of such freedom is not granted to any man here below, but it is only in society that it can be enjoyed at all; and freedom, in the common sense of that term, freedom from the bonds of law or of public opinion, is good only in so far as it helps man to attain that other freedom which is an end in itself, the end of all social organization.

Society exists only in a tempered mixture of constraint and licence. Where the individual has no choice in his actions, there will be no society; for where there is no individual will, there is no joint will; where the individual is free to do whatever he pleases, there is no society, for there can be no organization. The society best organized for the highest purposes is the freest society, and since the best organization is always relative to the character and circumstances of the persons organized, the desirable quantity of freedom from restraint is always relative to that character and to those circumstances. Any one who asks how much freedom is good for men, really asks how much freedom is good for his contemporaries and countrymen, and this question the statesman, rather than the philosopher, is bound to answer.

[183] Publicists no longer talk of man’s natural freedom, no longer attempt to establish an absolute measure of freedom for all times, countries, and peoples. They do not assume any abstract right to freedom. Allowing that no man has a right to anything save to that which is really good for him, they content themselves with trying to ascertain those principles which underlie all beneficial freedom and make it beneficial. This was the course adopted by Mr. Mill in his celebrated essay on Liberty. But it seems to me that he and many other authors of less ability and reputation occasionally lost sight of their admitted first premiss, and, whilst they advocated freedom on the ground of expediency, were not unbiassed by the doctrine of a former generation which asserted freedom as man's natural and indefeasible right.

Hickok, Laurens Perseus. 1885. A System of Moral Science. Ginn, Heath, and Co.: Boston.

[118] The duty is made plain by the distinct declaration of the law. Where ignorance might hesitate from its weak apprehension, the law speaks clearly; where practical principles are equivocal, the law expresses them distinctly and definitely; where practice must have some standard, and which from the nature of the case might be any one of many methods, the law directly settles which and how. Statute law, thus, in all practical measures, gives clearness to duty beyond what the reason in pure morality would supply. The state must legislate, and by legislation it meets the want of social freedom.

Politicus. 1886. New Social Teachings. Kegan Paul, Trench, and Co.: London.

[131-132] This is the conception which, in the commercial aspects, to which we will confine ourselves, is denoted by the phrase ‘freedom of contract.’ Let us apply this doctrine to the Irish landlord and tenant again. It claims for each, in the name of freedom, the right to make such bargain as he pleases, the consequent result of rent to landlord and profit to tenant being honestly theirs, with, perhaps, the proviso that no deception shall have been practised to obtain the result. We, then, have gained a morally right result. What is the actual result? As before stated, simply to hand over to the landlord the whole produce of the family labour, minus only that which is absolutely essential for bare subsistence. Poverty and ignorance have driven the tenant into substantial slavery, in which state ‘freedom of contract’ means freedom for the landlord to take whatever it is for his pecuniary interest to take. … Individualism in commerce means that whatever is gainable by competition is honestly mine, and that any interference with the freedom so to gain is dishonesty. The result we see to be that gross injustice results.

[137] We have stated the claim of Individualism to be that it alone (1) secures freedom; (2) is honest between the various members of a community; and (3), freedom and honesty being necessary to progress in civilization, it alone can secure that end. We find that a further State interference than Individualism will allow, even in its illogical moments, may (1) result in a larger freedom than laisser-faire would secure; may (2) give a higher honesty; and (3) may thus be the most direct path to a self-reliant humanity, and, generally, to progress in all the ends of civilization.

[161] We have seen that the Individualist denies the right of his fellows to limit his freedom, excepting so far as may be necessary to secure the like freedom to him. The aim is to preserve the individual for himself, and, possessing this greatest freedom of self-disposal, his conscience must determine how far he will sacrifice himself to the welfare of others.

Foxwell, Herbert Somerton. 1886. Irregularity of Employment and Fluctuations of Prices. Co-operative Printing Company Ltd.: Edinburgh.

[93] The almost complete anarchy of individualism through which we passed in the first half of this century may have been, hideous as it was, an essential stage in the evolution of society, —the travailing which was to give birth to the new era. We may go further, and admit that the principle may be held to imply a positive truth, which is truth in all ages. Individual freedom, when it is not exercised to the injury of others, is itself a social good of the highest importance. And were individual freedom unduly fettered by public control, that ‘tendency to variation,’ as the biologists call it, might be checked, which, in social as in organic life, is the first condition of development.

All this is true. But there is no greater mistake than to suppose that a mere negative policy of noninterference will secure general freedom to individuals. All it secures is the freedom of the strong to prey on the weak. The whole criminal law is a recognition of this fact. While, then, we must be careful that public control is not unintelligently and excessively applied, so as to destroy more freedom than it creates, it remains true that, in some form or other, reorganisation is emphatically the business of the present age, and that the strong prejudice in favour of a blind negative principle like laissez faire can do little but put obstructions in the way.

Bascom, John. 1887. Sociology. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York.

[158-159] Law must aim, under the moral sense, not only at justice between citizen and citizen, class and class, as the state finds them, but also, as a second effort, at a perpetual renewal of all the conditions of free, full, fair action between men, as these have been narrowed or unfavorably altered by the successes and defeats of the past.

Ritchie, David George. 1887. “The Political Philosophy of the Late Thomas Green,” Contemporary Review 51(Jun.): 841-851.

[849-850] Now it is obvious that freedom in this sense as the ideal end of the State is very different from the ‘freedom’ to which Locke considered that man had a ‘natural right’ in which a well-managed State ought to secure him. This freedom is the mere negative freedom of being left alone, and corresponds to the generic sense of freedom in morals. It is a mere means to the attainment of the freedom which is itself an end. This distinction shows what Green's attitude to the questions about State-action and laissez faire was likely to be. State-action, he holds, is expedient just in so far as it tends to promote ‘freedom’ in the sense of self-determined action directed to the objects of reason, inexpedient so far as it tends to interfere with this. … But, on the other hand, there is no a priori presumption in favour of a general policy of laissez faire, because in a vast number of cases the individual does not find himself in a position in which he can act ‘freely’ (i.e., direct his action to objects which reason assigns as desirable) without the intervention of the State to put him in such a position—e.g., by ensuring that he shall have at least some education. Terms like ‘freedom,’ ‘compulsion,’ ‘interference,’ are very apt to be misleading. As Green points out, “‘compulsory education’ need not be ‘compulsory’ except to those who have no spontaneity to be deadened” and it is “not as a purely moral duty on the part of a parent, but as the prevention of a hindrance to the capacity for rights on the part of children, that education should be enforced by the State.” The ‘interference’ may be interference in behalf of individual liberty—even in the negative sense of liberty. So also, when interference with ‘freedom of contract’ is spoken of, we must consider not only those who are interfered with, but those whose freedom is increased by that interference.

Lacy, George. 1888. Liberty and Law. Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey and Co.: London.

[128-130] ‘Free competition’ is only possible by the aid of that ‘freedom of contract’ which political economists and individualists hold to be the one panacea by which society is to be held together. We are told that if it is interfered with there will be an end to all industry. More, indeed, than this, for we are assured that the State will be practically disintegrated, and a condition of anarchy will presumably ensue. Let us then look a little at this wonderful nostrum. At the very first glance it is seen to be a complete delusion. For what is meant by freedom of contract, and what are the essentials to it? It must be perfectly obvious that the primary essential to freedom of contract between two individuals is that they must both be in similar positions in respect of the necessity, or otherwise, of entering into the contract. If to one it is a matter of indifference whether he enter into it or not, and to the other a matter of the greatest importance, it is manifest that that equality of circumstances necessary to equal freedom does not exist. To the extent of the greater or less importance to the one party of concluding the contract, to that extent is he compelled by his circumstances to conclude it. As applied to this transaction, therefore, freedom of contract is an absolute contradiction in terms. For the one party can demand his own terms, and the other is constrained to accept them. Freedom of contract is thus only possible between those whose circumstances are absolutely, or at furthest proximately, identical. The meaning of the expression is distinctly that both parties to it must be equally free to enter or to abstain. No other significance can be possibly attached to it. Although we may make believe to conjure with such terms as ‘equal,’ and ‘freedom,’ we must, when pushed to the point, acknowledge that they have each a special meaning, and cannot be applied to more than one idea. … This vaunted ‘freedom of contract,’ is therefore neither more nor less than the freedom to starve, and it is the grossest hypocrisy to apply such a term as freedom to it. It is distinctly a matter of coercion, without the remotest element of freedom whatever.

[155-156] In like manner, if the manufacturer has unrestrained freedom to exact his own terms, to work his hands so long as he pleases, in as insanitary conditions as he pleases, and with as dangerous machinery as he pleases, he holds power of life and death over his employés. If the shipowner has full freedom to send rotten and dangerously loaded ships to sea, he holds the same power. All such freedom is the slavery of others. The freedom of the ground-landlord to crowd insanitary dwellings on his land; the freedom of the building-lease owner to build rickety unwholesome houses, and to demand his own rent; the freedom of usurers to demand their own interest; the freedom of brewers and distillers to make and sell poison; even the freedom of the butcher and baker to exact their own prices for the necessaries of life, all come under the same head. It is one gigantic system of the compulsion of the weak by the strong.

[160-161] Thus even if Liberalism ever had a sincere desire for general freedom, which I maintain that the evidence does not warrant, it defeats its own end. It may have freed large numbers of people from the power of the landlords but it has only done so in order to step into the landlords shoes—for whether or no it had that special intention, it has done so in fact. In place of an aristocracy it has created a plutocracy, and though the latter has undoubtedly done immensely more for civilisation than the former, in that it has created wealth which by more judicious distribution might be of inestimable value to mankind, yet the actual organisation it has effected is not a whit better than that which preceded it. … There is no more real freedom from restraints now than there was before the Liberal party came into being. Many disabilities have been removed, but in place of them have been substituted innumerable restraints, which owe their existence solely to the nature of capitalism and could have none under any other system.

[162-163] Compulsion is everywhere, and the only freedom is that if the ways of the trade are not complied with it can be left. The freedom then is not the freedom to do or to refrain in every particular case, but the freedom to do or refrain in respect of the cumulative demands of a particular class. But in the case of small traders and wage-earners, who have to get a living by their own personal efforts, this freedom finally resolves itself into the freedom to do, not one particular thing, but a large class of things, or to starve.

Kirkup, Thomas. 1888. An Inquiry into Socialism. Longmans, Green and Co.: London.

[155-156] It is very generally assumed that socialism would involve a great curtailment of individual freedom. … Now nothing can be more certain than that under the present system the freedom of the mass of men is merely nominal. If attained at all, it can be attained only at the expense of security, at the risk of sacrificing the means of subsistence; it is a choice of working under the prescribed conditions, which are frequently unhealthy, degrading and dangerous, or of starving. Not seldom there is no choice at all, but compulsory starvation and the wretchedness of pauperism. … Such freedom is a mockery and delusion. There can be no substantial or desirable freedom that is not based on economic security, on the possession of a home, and on well-established means of subsistence and of cultivation both of body and mind.

[156] Our present system of industrial relations is in theory regulated by free contract. In a country where land and capital are virtually the monopoly of a class, there must be a vast multitude of contracts that are only nominally free. When land is required for building or industrial purposes, the landholder can exact his own terms; the contract is not free. … He has to deal with a powerful monopolist for that which is to him essential and indispensable. Scarcely anywhere or at any time, even with the unrestricted right of combination, does the workman meet the capitalist on equal terms.

[184] Like the democracy, socialism aims at the realisation of freedom for the mass of mankind; not the negative freedom of laissez-faire, but a substantial, well-ordered freedom; not the one-sided and delusive freedom of individualism, but one that has regard to the economic and social needs of man; freedom under moral and economic conditions suited to the fuller and more harmonious development of human beings; freedom wedded to moral law, to art and knowledge.

Haldane, R. B. 1888. “The Liberal Party and its Prospects,” The Contemporary Review 53(1): 145-160.

[154] The great error which has been made, and which has led to much of the popularity of what is currently called Socialism…has been its identification with the bare fact of a departure from the principles of laissez faire… The truth is, that it is not a mere departure from the principle of laissez faire which sensible people mean when they object to propositions as Socialistic of economically unsound! Such departures are even recognized as essential for the promotion of real freedom between contrasting parties.

Richmond, Wilfrid John. 1888. Christian Economics. E. P. Dutton and Co.: New York.

[267-268] Freedom was the keynote of the gospel of Political Economy as preached by Adam Smith. This freedom was the freedom of production, industry, and trade from the artificial restraints of law, from those restraints, especially, which were dictated by the false idea that money, the means of the exchange of wealth, was wealth itself, and which, under this idea, enriched a certain number of traders at the expense of the general prosperity of the community. What was demanded was, that law should leave the economic machine to work by itself: the result was anticipated that there would be a great increase in the amount of wealth produced, and in the prosperity of the community at large.

We have to set forth a new demand, that the economic motive should be set free from any restraints which are imposed upon it in the working of the economic machinery, free to attain the result at which it really aims, happiness in the enjoyment of wealth. Wealth is its end—not the production of wealth only, but its just use, and its right enjoyment—wealth, as it contributes to the well-being of those who produce it. This freedom differs from the other in two respects. It is not merely negative—the removal of restraints; it is freedom to do something—to enjoy. Again, it is human; it is freedom, not for a system only, but for men. This freedom of enjoyment it is the aim of economic morals to secure. A man’s duty in regard to wealth may be said to be so to act as to forward its highest enjoyment. Wealth reaches its end in being enjoyed.

Webb, Sidney. 1889. “The Historic Basis of Socialism” Fabian Essays in Socialism edited by G. Bernard Shaw. The Fabian Society: London.

[41] Women working half naked in the coal mines; young children dragging trucks all day in the foul atmosphere of the underground galleries; infants bound to the loom for fifteen hours in the heated air of the cotton mill, and kept awake only by the overlooker’s lash; hours of labor for all, young and old, limited only by the utmost capabilities of physical endurance; complete absence of the sanitary provisions necessary to a rapidly growing population: these and other nameless iniquities will be found recorded as the results of freedom of contract and complete laisser faire in the impartial pages of successive blue-book reports. But the Liberal mill-owners of the day, aided by some of the political economists, stubbornly resisted every attempt to interfere with their freedom to use ‘their’ capital and ‘their’ hands as they found most profitable, and (like their successors to-day) predicted of each restriction as it arrived that it must inevitably destroy the export trade and deprive them of all profit whatsoever.

Clarke, William. 1889. “The Industrial Basis of Socialism” Fabian Essays in Socialism edited by G. Bernard Shaw. The Fabian Society: London.

[86-87] Capitalism is becoming impersonal and cosmopolitan. And the combinations controlling production become larger and fewer. Baring’s are getting hold of the South African diamond fields: A few companies control the whole anthracite coal produce of Pennsylvania. Each one of us is quite ‘free’ to ‘compete’ with these gigantic combinations, as the Principality of Monaco is ‘free’ to go to war with France should the latter threaten her interests. The mere forms of freedom remain; but monopoly renders them nugatory. The modern State, having parted with the raw material of the globe, cannot secure freedom of competition to its citizens; and yet it was on the basis of free competition that capitalism rose. Thus we see that capitalism has cancelled its original principle—is itself negating its own existence.

[98] Now what does this examination of trusts show? That, granted private property in the raw material out of which wealth is created on a huge scale by the new inventions which science has placed in our hands, the ultimate effect must be the destruction of that very freedom which the modern democratic State posits as its first principle. Liberty to trade, liberty to exchange products, liberty to buy where one pleases, liberty to transport one's goods at the same rate and on the same terms enjoyed by others, subjection to no imperium in imperio: these surely are all fundamental democratic principles. Yet by monopolies every one of them is either limited or denied. Thus capitalism is apparently inconsistent with democracy as hitherto understood. The development of capitalism and that of democracy cannot proceed without check on parallel lines. Rather are they comparable to two trains approaching each other from different directions on the same line. Collision between the opposing forces seems inevitable.

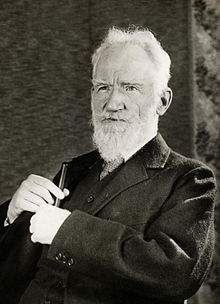

Bernard Bosanquet (1848 – 1923) was an English philosopher and political theorist, and an influential figure on matters of political and social policy in late 19th and early 20th century Britain. His work influenced – but was later subject to criticism by – many thinkers, notably Bertrand Russell, John Dewey and William James.

Bosanquet, Bernard. 1889. Essays and Addresses. Swan Sonnenschein and Co.: London.

[103] Nothing is more shallow, more barbarously irrational, than to regard the progress of civilization as the accumulation of restrictions. Laws and rules are a necessary aspect of extended capacities. Every power that we gain has a positive nature, and therefore involves positive conditions, and every positive condition has negative relations. To accomplish a particular purpose you must go to work in a particular way, and in no other way. To complain of this is like complaining of a house because it has a definite shape. If freedom means absence of attributes, empty space is ‘freer’ than any edifice. Of course a house may be so ugly that we may say we would rather have none at all.

Ely, Richard T. 1889. An Introduction to Political Economy. Chautauqua Press: New York.

[35-36] Take the one economic factor of labor. It is found in a condition of slavery, in a condition of serfdom, and in a condition of free contract. But these are only names for the three general conditions in which labor has been found, and within each one of these conditions there has been a multitude of changes. Slavery has assumed a vast variety of forms, some extremely harsh and some extremely mild, with almost infinite gradations between the two extremes. Serfdom at times appears as harsh as slavery, and it is also found in forms which differ little from freedom, and which are doubtless in some respects superior to the condition of the ordinary laborer who is free to make his own bargains, or who, as we say, lives under the regime of free contract. Free contract in its turn means many different things: sometimes, indeed, the oppression by the employee of the one who employs labor, but oftener the practical dependence of the laborer on account of the pressure of economic necessity; at times, indeed, a dependence which virtually amounts to slavery, as has been seen in the case of tailors in London employed by so-called ‘sweaters,’ or small contractors, who have reduced their workmen to such a condition that perhaps a dozen have only one coat among them, and they are kept prisoners in the dens where they work.

Lilly, William Samuel. 1889. A Century of Revolution. Chapman and Hall: London.

[36] The only legitimate limit to the freedom of each is that which is necessary for the equal freedom of all. … This is no a priori abstract idea, such as that wherewith the maker of paper constitutions starts, when he sets himself to build up his house of cards. It is a principle, which is the most concrete thing in the world; the quintessence of the facts from which it is deduced; the very law of their succession and connection as manifested in their working.

[37-38] We may say then, as the result of our argument, that Liberty [is] freedom from constraint in the action of our faculties; that, considered in its end, it is the exercise of personality; that its indispensable condition is a certain stage of intellectual and spiritual development…in which a man shall be capable of tending consciously towards the realization of personality; and that the law of its tendency is moral. ‘When we measure the progress of a society by its growth in freedom,’ the late Professor Green has well observed, ‘we measure it by the increasing development and exercise, on the whole, of those powers of contributing to social good… Freedom, in all the forms of doing what one will with one's own, is valuable only as a means to an end. That end is what I call freedom in the positive sense: in other words, the liberation of the powers of all men, equally, for contributions to a common good.’

This is real freedom. This is the only liberty worthy of that august name. This rational liberty all social institutions and political machinery should subserve; and they are of value only in proportion as they do subserve it.

Anonymous. 1889. “French and English Jacobism,” The Quarterly Review 168(336): 532-558.

[535] But, at the outset, we are confronted with another question: what do we mean by human liberty? Shall we, with Mr. Herbert Spencer, take ‘real freedom’ to ‘consist in the ability of each to carry on his own life without hindrance from others, so long as he does not hinder them?’ Surely that is a most inadequate conception of ‘real freedom.’ For such freedom is merely negative. It has no root in itself. It is the freedom of the wild beast, the savage; physical, not rational; chaotic, not constructive. Real freedom, positive liberty, means a great deal more than that: it means the possession of an interior rule, of a moral curb. It is the endowment which specially distinguishes the civilized man. It is the peculiar product, the chief object of polity. …

‘Freedom,’ writes the late Professor Green, ‘forms the true goal of social effort. … The ideal of true freedom is the maximum of power for all members of human society alike to make the best of themselves. … That end is what I call freedom in the positive sense: in other words, the liberation of the powers of all men, equally, for contributions to a common good. …When we speak of freedom as something to be so highly prized, we mean a positive power or capacity of doing or enjoying, something worth doing or enjoying, and that, too, something which we do or enjoy in common with others.’

This is ‘real freedom,’ as we account of it.

Bax, Ernest Belfort. 1891. Outlooks from the New Standpoint. Swan Sonnenschein and Co.: London.

[66] What is the crucial distinction between Liberalism or Radicalism and Socialism? This is a question very often asked. That they are actually often opposed is not to be denied. But the general opinion among advanced Liberals seems to be that Liberalism, if its principles are thoroughly carried out, is not in any necessary conflict with Socialism. We propose to examine this position with special reference to the economic basis respectively of Liberalism and Socialism. The Liberal party has always claimed to be the party of progress, to be the exponent of the progressive lines of social and political development at a given epoch, and, as such, to be opposed to the party of reaction. This may be termed the negative side of Liberal theory, and so long as it maintains this attitude as the party in the vanguard of progress, it must necessarily become identical with Socialism—i.e., from the standpoint of Socialists. But here comes the crux. If Liberalism becomes identified with Socialism, it surrenders bodily all that has hitherto formed the positive side of its theory, and, indeed, what has hitherto given it the reason of its being. It has up till now placed the freedom of the individual as the professed aim of all its measures, and as its basal principle. But does not Socialism also aim at the freedom of the individual we shall be asked? Certainly. But the question is, what do Liberals (for the most part) understand by their freedom of the individual, or individual liberty, and why have they always made it such a strong point in their political faith? The answer is, they meant by individual liberty, first and foremost, the liberty of private property as such, to be uncontrolled in its operations by aught else than the will of the individual possessing it. What was cared for was not so much the liberty of the individual as the liberty of private property. The liberty of the individual as such was secondary. It was as the possessor and controller of property that it was specially desired to assure his liberty. Indeed, in the extreme form of ‘Liberal’ theory and practice, as embodied in modern legislation, the individual appears merely as the adjunct of property.

[69-70] But I shall hope to show, further, that progress has now turned a corner, so to speak; that the removal of all hindrances to the acquirement of wealth other than what is based upon conscious fraud or open force; that the absolute right of the individual over the property he has acquired or inherited—in short, that security and freedom in the tenure of private property is no longer synonymous with individual liberty, but often with its opposite; that individual liberty now demands the curtailment and the eventual extinction of the liberty of private property, and that Liberalism, in so far as it aims at maintaining the liberty of private property, is reactionary and false to the principle which it has always implicitly or explicitly maintained, of the right of each and every individual to a full and free development. In so far as Liberalism does this, in so far as it assumes as axiomatic a state of society based on unrestricted freedom of private property, and proceeds to adjust social arrangements solely or primarily in the interests of the owners of private property—in so far, Liberalism and Socialism are death enemies. Liberalism has been negatively described by Sir Henry James as being alike opposed to Toryism and Democracy, and this is, I think, no unfair description of Liberalism during this century. Liberalism has historically opposed itself alike to Toryism, landed interest, and democracy, working-class interest, whenever that interest appeared as a distinct political party. It has been the political creed of the middle-classes, which has used the war-shout of individual liberty as a means for the acquirement of individual property. The individual liberty now desired by the Socialist is the liberty of the individual as man, and no longer his liberty as mere property-holder.

[77] Liberalism was therefore now entering upon a new phase. The middle-class was beginning to see that its interest lay in a fuller carrying-out of its ground-principles, rather than as heretofore in their merely tentative and limited application. The working-man, like everyone else, must be freed from artificial restraints in the acquirement of wealth, must be allowed free liberty to make what contract he pleased; this was the claim, at least, of the more advanced section of the party. He must be made equal before the law. Now the working-man for a long time heeded the music of the Liberal syren. Chartism went to pieces. The new Liberalism carried all before it.

[78-79] Now the Socialist, in contradistinction to the Liberal, recognises to the full this contradiction between the two individualisms, the individualism which centres in personal property, and to which Socialism is opposed, and the individualism which presupposes the abolition of private property, at all events in the means of production, and which is identical with Socialism. He sees that the first is a purely abstract and formal individualism which sacrifices the real freedom of the individual to his merely nominal freedom. He finds that the workman is the slave of economic forces beyond his control, and that the way of real freedom for the individual, as for the society, lies in a revolution in economic condition which must involve the negation of the liberty of private property.

[86-87] The great thing which now oppresses men is, not the privilege of status, but the privilege of wealth. It is not the legal position into which a man is born that weighs him down, it is the contract he is compelled to make of his own free choice (if you will excuse the ‘bull’). Progress therefore on the old lines of individual freedom before the law has plainly reached, or is fast reaching, an impasse beyond which it is impossible, and would be useless if it were possible, to go. Liberal individualism is therefore played out. Progress towards freedom, in short, has, as I said at the beginning of this lecture, ‘turned a corner.’ Its old position has landed it in a contradiction, inasmuch as the attainment of the maximum of formal liberty has produced a maximum of real slavery. Free contract under a system of unrestricted individual property holding has strangled liberty. We are to-day struggling with this fell contradiction. To suppress one of its terms is impossible.

Bax, Ernest Belfort. 1891. The Religion of Socialism. Swann Sonnenschein and Co.: London.

[34] In the present day the abstract, the nominal freedom of the individual is complete. But individualism has no sooner shaken itself free from the supports which, though they may have cumbered it in its advance, yet did at least keep it from falling; it has no sooner completely realised itself, than its death-knell is rung, and it finds itself strangled by the very economical revolution which had rendered its existence possible. For that revolution which has brought about an absolute separation of classes, has deprived the one class of all individuality whatever, albeit their abstract freedom still remains to mock them.

Gunton, George. 1891. Principles of Social Economics. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York.

[417-418] The contention that trades unions destroy the right of individual contract and limit the laborer’s freedom has a plausible seeming, but it is singularly superficial. If it be true that combination destroys the freedom of the laborer, why does it not also destroy that of the capitalist. It will hardly be contended that capitalists who have steadily integrated into larger and larger combinations are less free than formerly; one great complaint against them is that they are having too much freedom. It is true that labor combinations have steadily increased during the last fifty years, and it is equally true that the laborers’ industrial, social, and political freedom has increased more during that period than ever before.

[419] The mistake in this attitude arises from a misconception of what constitutes freedom. As already observed, freedom does not consist in the negative permission to do but in the positive power of actual doing. The essence of freedom is power, and the source of economic and social power is wealth. Nothing can furnish the motive to associate but the fact that association increases the power to obtain desired objects. The history of freedom is the history of progress, and the history of progress is the history of industrial, social, and political integration or combination. Every movement towards freedom is a movement towards greater economic and social interdependence between individuals. Interdependence involves mutual helpfulness, which in turn furnishes security of rights and the maximum freedom of action. The difference between freedom furnished by savagery and that secured by society is that the former affords the freedom to injure while the latter gives freedom only to help our fellow-man, and thereby benefit ourselves. If trades unions were inimical to the laborers’ freedom we should find more individuality and freedom among unorganized than among organized laborers. The facts, however, are everywhere the reverse. … It is not correct therefore, either theoretically or historically, that labor combinations tend to destroy the laborers’ freedom.

Ritchie, David George. 1891. Principles of State Interference. Swan Sonnenschein and Co.: London.

[92] The head of the household, if left to himself to act ‘like the Cyclops’ in patriarchal manner, might exercise his patria potestas in a way which would interfere with the just liberty—i.e. what we have come, or are coming, to regard as the just liberty—of wife, children, and servants. The State steps in to protect them by direct legislation, or by sanctioning legal remedies against the exercise of customary privileges with which in the good old days it would never have dared to meddle, or dreamt of meddling. The trades guilds exercised an authority over individuals to which the State has gradually put an end. The State has restrained religious bodies from exercising the control they wished over the opinions and conduct of individuals. We are beginning to find out that the powers of gas and water companies, and the relations between landlord and tenant, between employer and employed, nay, even between parent and child, frequently need State interference in the interest of individual freedom. Yet all these various subordinate associations of men contribute their share to the formation of that vague totality which we call ‘public opinion.’

Dewey, John. 1891. Outlines of a Critical Theory of Ethics. Register Publishing Co.: Ann Arbor, MI.

[158] Negative Aspect of Freedom. The Power to be governed in action by the thought of some end to be reached is freedom from the appetites and desires.

Ritchie, David George. 1895. Natural Rights. Swann Sonnenschein and Co.: London.

[138] It would be easy to multiply examples of the ambiguities of the words ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom.’ …The ‘liberties’ of corporations, classes, or individuals, mean their special privileges, and thus involve considerable interference with the ‘liberty’ of the non- privileged. ‘Freedom of contract’ may result in a practical bondage of one of the parties to the other.

[147] A few strong, well-armed men might be quite willing that every one should have an equal right to kill and plunder; but this willingness of the brigand to adopt the formula of Mr. Herbert Spencer would not (in the judgment of most persons) justify a settled modern society in going back to

‘the good old rule . . . the simple plan,

That they should take who have the power,

And they should keep who can.’The principle of equal freedom, if taken as the ultimate basis on which the fabric of law and government is to be built up, would either compel a complete abstinence from all action on the part of every individual—that would be one way of every one having an equal right to do everything,—or it would mean the equal right of every one to do everything in the sense of Hobbes, i.e. the war of all against all.

Mackenzie, John Stuart. 1895. An Introduction to Social Philosophy. Macmillan and Co.: New York.

[321n.2] Cf. Bryce’s American Commonwealth, Vol. 1II., p. 545, where it is pointed out that the freedom of American life does not lead to variety. On the other hand, however, it might be urged that American life is in this respect the very type of what might be expected under a socialistic regime; for the freedom which the American citizen enjoys is precisely that which the socialist would grant—‘the right of doing whatever the law permits.’ It is freedom of the people as a whole, rather than freedom of the individual citizen.

[283] In the battle of life more execution is often done with the elbows than with the fists; and pure laisser faire, instead of freeing us from the interference of one another, leads simply to the most intense of all struggles, in which the less capable are overcome and subjected by the more capable—or rather the less fit, who in a higher sense are sometimes in reality the most capable, by those who are more fit for the struggle of life in that particular style. … The result of this is, as we had occasion to point out before, the exploitation of man by things. Men, in endeavouring to free themselves from one another, become enslaved by their own inventions. For this reason, if for no other, pure liberty in this sense is an impossibility. It ‘passes over into its opposite,’ as all such abstractions tend to do.

At the same time, it would be rash to conclude that there is no sense in which it may rightly be maintained that freedom is our ideal. What we find is rather this, that freedom from our fellowmen is not in reality freedom, so long as nature remains our enemy to such an extent that we require to act together in the effort to subdue her.

[284] Freedom, in fact, can mean for us nothing but that, in Hegelian language, we are ‘determined by the absolute idea throughout.’ ‘Law alone can give us liberty.’ … Children, however, in whom it is recognised that the rational nature is not yet fully developed, are by general consent subjected to an external rule; and so long as there is any truth in the saying that men are but ‘children of a larger growth’…they cannot be freed from a certain amount of social regulation. As the parent is the embodiment of the universal self for the child, so is society the embodiment of it for the man. And thus we are naturally led from the individualistic to the socialistic ideal.

McKechnie, William Sharp. 1896. The State and the Individual. James McLehose and Sons: Glasgow.

[309] The second individualistic assumption which requires examination is that whatever is gained to authority is lost to freedom and vice versa; just as one vessel might be emptied by pouring its contents into another. In reality the facts are exactly the reverse. The stronger the government becomes, the greater, caeteris paribus, is the liberty of its subjects. It has been already pointed out that the coercion of government is a way of escape from the worse coercion of unorganized society, of local prejudice, and, worst of all, of anarchy.

[317-318] Is no similar conception of positive freedom possible in the sphere of the State? Undoubtedly it is, for political freedom means subjection to the laws of a rational government, which frees individuals from subjection to a chaos of warring wills. It means the substitution of the coercion of Parliament for that of free competition, of the national will for that of the county or parish or trades union, of wisdom for ignorance. It is only when a negative and abstract conception is formed of liberty, that government is necessarily its foe. It is by taking this inadequate view of freedom that Sir John Seeley is led to make the opposition final and irreconcilable. ‘Liberty, in short,’ he says, ‘in the common use of language, is opposed to restraint, and as government in the political department is restraint, liberty in a political sense should be the opposite of government. … Liberty being taken as the opposite of government, we may say that each man’s life is divided into two provinces, the province of government and the province of liberty.’ Such reasoning, founded as it is on individualistic assumptions, would lead to the conclusion that the savage is more ‘free’ than the subject of a civilized State, because the number of restraints placed upon him is less.

Mr. Herbert Spencer’s definition may be profitably compared with Professor Seeley’s, as both have fallen into the same error. ‘The liberty which a citizen enjoys is to be measured, not by the nature of the governmental machinery he lives under, whether representative or other, but by the relative paucity of the restraints it imposes on him.’ Now, this is to take an artificial and mechanical view of liberty, and to determine the degree of freedom or of bondage by merely adding up the sum of restraints irrespective of their character. It is, however, the nature and not the number of these restraints that is the important point. To obey the uniform laws of a rational government is freedom, whereas to be at the mercy of the capricious dictates of a Nero is slavery. Freedom, when understood in a positive sense, is not lawlessness.

Gunton, George. 1897. Wealth and Progress, seventh ed. D. Appleton and Co.: New York.

[205-206] Freedom does not consist in the mere absence of legal barriers, but in the actual power to go and to do. The poor can never be free in any true sense of the term. Whoever controls a man’s living can determine his liberty. Freedom means independence, which nothing but wealth can impart.

[230-231] But before a satisfactory answer to the above question can be given, it is necessary to understand what constitutes social opportunity. In the sense that the expression is here used, opportunity, like freedom, does not consist of the mere absence of legal or arbitrary limitations. A man is not free to go and to do, simply because statute law does not forbid him, nor even by virtue of its expressed permission to do so. The man whose livelihood depends upon the will of another has no more freedom than if he were bound by statutory enactment. Whoever controls a man's living can control his liberty. To be restricted, by whatever means, to choosing between obedience to the will of another and starvation, is not freedom. The worst form of chattel slavery that ever existed could not prohibit the slave from choosing between obedience and death. The freedom to do implies not only the right, but also the power to do. To simply remove imposed restrictions, to make access to certain places and things legally possible, is not necessarily creating opportunity.

Ball, Sydney. 1898. “Individualism and Socialism II,” The Economic Review 8(2): 229-35.

[230] …[T]he phrase ‘economic independence and freedom of the individual’ refers to the divorce of the worker from the means of production, and connotes something more than the formal but ineffectual freedom to which certain theorists of Liberalism have limited the conception. To adopt a Hegelism, under a system of private Capitalism, only ‘some men are free.’

Gronlund, Laurence. 1898. The New Economy. Herbert S. Stone and Co.: Chicago.

[73] Now, what does it mean to be ‘free’? We have in our English language two words: ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom,’ that we unfortunately are in the habit of using indiscriminately. And yet, we may be sure, that there is a difference, even an important difference, between them, just as we in the next chapter shall see there is between individualism and individuality. Liberty, in the first place, is a Latin word, while freedom is of Anglo-Saxon origin; liberty, next, is a purely negative term, but freedom is decidedly positive. Liberty simply denotes the absence of restraint; to be ‘at liberty’ means not to be controlled. Now it is easy enough to see, as soon as we only reflect, that the condition of not being restrained may under some circumstances be a very bad one, as under others it is a very good one; but we rarely think of this, for liberty happens to be a splendid illustration of the magic power which mere words may have over us. We say deliberately that liberty has unfortunately in our country degenerated into a most pernicious condition. Some time ago an employer, who liked to roll ‘liberty’ under his tongue, was as a witness asked to give his definition. He answered: ‘Why, liberty is the right of an American to do as he pleases,’ and added, ‘this is the American ideal of manhood.’ Well, unfortunately he was right; our competitive system has given some Americans, a very few, such a right, and it is looked upon by altogether too many as our ‘ideal of manhood.’

[75-76] But freedom, strictly speaking, cannot be abused. It is a positive acquisition, as was already said. … That is to say, power is an essential, integral constituent of freedom; freedom is power, as also Locke observed. Freedom once was a privilege, just as property now is. … The freedom we mean is Kingsley’s ‘true freedom,’ while liberty is his ‘false freedom;’ Wordsworth calls the latter ‘unchartered freedom.’ Now, freedom has in theory been made the inalienable right of all our decent people; practically, however, the very reverse obtains; the masses of our citizens are positively un-free; and they are that, really and truly, because a few amongst us are altogether too much ‘at liberty.’ We cannot enjoy our right to freedom, because our powerful fellow-citizens abuse their liberty.

[76] We said that freedom is closely connected with economics; it is dependent upon our enjoying security and independence in the economic sphere. But free competition is a condition where none but the successful few are free. Yet we can not lead moral lives at all, unless we are free, unless we have the power of freedom. Hence, not liberty, not equality, but freedom is the ideal of Collectivists and should be ‘the ideal of manhood’ for us all. And it is freedom that the new education will have for object.

Ely, Richard T. 1899. “Political Economy,” in Political Economy, Political Science and Sociology, ed. by Richard T. Ely. The University Association: Chicago.

[29] Personal freedom then signifies that relations are determined by bargains which each one supposedly makes for himself. It would seem that legal freedom to make the bargains which one pleases must give in reality personal freedom. It is the theory of free contract that, as a matter of fact, it does terminate in actual freedom. Personal freedom must be considered in several particulars in order to understand the true nature of the conditions which actually exist in industrial society. First of all it should be observed that true freedom is not merely negative, but is rather positive.

[30] The idea of freedom is a positive opportunity to develop or unfold all one’s powers, to make the best of one’s self, and to contribute according to one's faculties to the common good.

Vail, Charles Henry. 1899. Modern Socialism. Commonwealth Co.: New York.

[142-143] Individual freedom consists in the opportunity to develop real individuality and true personal character. This is impossible where each is fighting for himself and against his neighbor. A true social environment is the first requisite to individual development and real freedom. The acquisition of freedom necessitates peace, order, and organization. Socialism alone furnishes the conditions for individuality and personal freedom. To-day we are under the greatest tyranny of which it is possible to conceive, —the tyranny of want. It is this whip of hunger that drives men to work long hours and in unwholesome occupations. It is here that we find the basis of servitude. Slavery is economic dependence on the oppressor. We require liberty not only intellectually and morally but economically. The first two have been recognized as abstract rights, but both have been practically nullified through the absence of the last. We must secure economic freedom to be assured of intellectual and moral freedom. … The man who has no work, or who must submit to wages dictated by a corporation in which he has no voice, —a wage which means only a bare subsistence, —need not fear the abrogation of his freedom. Personal liberty for such is already abrogated, and in many instances political liberty also, for the dictation of corporations in the use of the franchise is something execrable. A man thus tyrannized over is not free. Any man who for ten hours a day is at the beck and call of a master has not yet attained his emancipation. True freedom can only be realized in the Co-operative Commonwealth.

[144-145] Freedom, as we have seen, would not be as much restrained under Socialism as it is now under capitalism. No one would claim that labor is free to-day. The industrial worker is only a link in the chain and is subjected to many rules and regulations. It is not only freedom of labor but freedom from labor that Socialism seeks. This freedom, which results from the common ownership of machinery, would secure to the laborer that leisure so much desired. Socialism would enable men to live as men, and secure to each the best opportunities for free development and movement. The objection that Socialism would destroy liberty either within or without the economic sphere is wholly without foundation.

Hobson, John Atkinson. 1900. “The Ethics of Industrialism” in Ethical Democracy edited by Stanton Coit. Grant Richards: London.

[82] The eulogists of laissez faire and the free trade economy have doubtless been too indiscriminate in their exposition of this unseen harmony of interests. But making due allowance for this, the economic changes summed up in the Industrial Revolution must be accounted great liberating forces. The competitive ideal, that every man should have his chance to do the best work for himself and for the world, was not indeed attained, but some definite steps were taken towards it, by the breaking down of ancient obstructive barriers. In spite of all the misery and degradation which accompanied, and in part resulted from, the earlier phases of the change, modern industrialism may be accredited with a real increase in the sense aggregate of individual freedom, not merely in the negative of abolition of restraints, but in the positive sense of an increase of opportunities for the attainment of a good human life.

Huxley, Leonard. 1900. The Life and Letters of Thomas H. Huxley Vol. 1. Appleton: New York.

[384-385] Suppose, however, for the sake of argument, that we accept the proposition that the functions of the state may be properly summed up in the one great negative commandment– ‘Thou shalt not allow any man to interfere with the liberty of any other man’ –I am unable to see that the logical consequence is any such restriction of the power of government, as its supporters imply. If my next-door neighbor chooses to have his drains in such a state as to create a poisonous atmosphere, which I breathe at the risk of typhoid and diphtheria, he restricts my just freedom to live just as much as if he went about with a pistol threatening my life; if he is to be allowed to let his children go unvaccinated, he might as well be allowed to leave strychnine lozenges about in the way of mine; and if he brings them up untaught and untrained to earn their living, he is doing his best to restrict my freedom, by increasing the burden of taxation for the support of gaols and workhouses, which I have to pay. The higher the state of civilization, the more completely do the actions of one member of the social body influence all the rest, and the less possible is it for any one man to do a wrong thing without interfering, more or less, with the freedom of all his fellow citizens.

Herkless, William Robertson. 1901. Jurisprudence or the Principles of Political Right. William, Green, and Sons: Edinburgh.

[31] Reflection removes any semblance of paradox from the conclusion that the object of the state is the state itself. Because freedom is the essence of spirit or self-conscious being, the absolute final aim is freedom. Law, morality, government, are the actual or concrete truth of freedom. They exist only in and through the state. Thus the state, as expressing the absolute final aim, is an end in itself. It exists for itself, and not as means or instrument to any other end. In other words, the object of the state is the state itself.

Ely, Richard T. 1901. Introduction to Political Economy. Eaton and Mains: New York.

[64] It is well in this connection to reflect on the real nature of freedom. In a positive sense freedom is intelligent obedience to wise law, but frequently, perhaps even commonly, it signifies mere absence of restraint upon our actions, and is thus negative. It may be compared to an empty vessel. Its value depends upon what we put into it. Absence of restraint can hardly be called a good in itself. It may be a curse, or it may be a blessing. It gives opportunity for the development of our faculties to a full and harmonious whole; yet, if we are not ripe for such self-governing as would be made necessary, it may involve our degradation. Children are not fit for it, and their development can better be secured under the controlling influence of a higher authority. Not all nations are fit for it. The Declaration of Independence was the assertion before the world that we were fit for free and uncontrolled self-development. American democracy means the ripeness of Americans for political freedom.

Holyoake, George Jacob. 1901. “Anarchism,” The Nineteenth Century and After 50(296): 683-686.

[684-685] The philosophical anarchists adopt, or accept, the name, but have no anarchy in them. They are against conventional government—not from malice, but because they think self-government nobler. What they seek is unlimited freedom, which, if set going to-morrow, would not last a month. They hold that free association will be the ultimate form of society. There is no disquietude in that—but the distance to it is distressing. They are for voluntary, not compulsory society. Their passion is for absolute individual freedom. It may be described as individuality run mad—as men and things go.